The terror of the flying lettuce

One of the greatest challenges I face when traveling abroad isn’t the language barrier—it’s the table manners. Specifically, the terrifying absence of Japanese chopsticks.

How on earth do you eat a lettuce salad with only a fork? Every time I try, I’m paralyzed by fear. One wrong move and a springy leaf flips like a catapult, splattering dressing all over my shirt. And don’t even get me started on other Asian utensils. Korean metal chopsticks, for instance, are my nemesis. By the time I finish a bowl of slippery noodles in Seoul, my shirt usually sports a psychedelic pattern of soup stains.

I suspect that anyone who eats comfortably without Japanese chopsticks must be either a professional tester for laundry detergents or an avant-garde fashion designer trying to “finish” a garment through a series of tactical food spills. Either way, their ability to accept stains as a natural part of the dining experience makes them, in their own way, invincible.

The “pinch” vs. the “scoop”

The world’s dining habits are roughly split into three: 40% eat with their fingers, 30% with spoons/forks, and 30% with chopsticks. While this is largely dictated by staple foods, I firmly believe Japanese chopsticks are the peak of culinary evolution.

They do everything fingers can do, but with the added “superpower” of pinching boiling hot food without pain. Granted, they can’t scoop soup, but we Japanese solved that centuries ago by simply lifting the bowl to our faces like a civilized mug. Give me a pair of well-balanced Japanese chopsticks, and I would confidently wear a brand-new white silk shirt to a tomato sauce pasta feast.

The monogamy of chopsticks: A strict relationship

What makes Japanese chopsticks truly unique is that they are “personal.” In Japan, we don’t just share utensils like common peasants—even within a family, everyone has their own dedicated pair of chopsticks and their own rice bowl. It is a strictly monogamous relationship between a human and their wood.

Speaking of “strict,” you should be very careful about how you hold them. In Japan, there is zero diversity or tolerance when it comes to chopstick technique. You are under constant surveillance; holding them incorrectly can seriously damage your “social credit score.”

If you’re on a first date, I recommend the “George Washington’s Cherry Tree” strategy: confess immediately. Admit that your chopstick skills are a little eccentric right at the start. By being honest about your faults, you might just cover up the technical points you’re about to lose with the points you gain for sincerity.

A stubborn attachment to texture

Japanese chopsticks are basically made of wood and are sharply tapered at the tip for surgical precision. Is wood the “perfect” material? Not technically. You have to wet them so the rice doesn’t stick, and they take forever to dry. Plus, if you have kids, they will inevitably bite and splinter the tips.

And yet, we cannot let go of the wooden touch. Perhaps it’s because we are obsessed with the texture, the warmth, and the “soul” of the material. This same stubborn, hyper-particular attachment to wood is exactly what drives the craftspeople at CondeHouse. We don’t just make furniture; we make objects that you’ll want to claim as “mine,” just like your favorite pair of chopsticks.

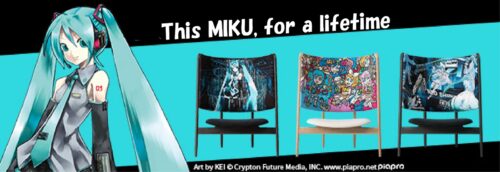

I confess that I feel naked without my Japanese chopsticks—because in a world of clumsy forks and slippery metal, only the surgical precision of wood feels like a true extension of my soul. At CondeHouse, we share this obsessive, monogamous attachment to the material. We don’t just build furniture; we create ‘personal’ objects that, like your favorite pair of chopsticks, become an indispensable part of your identity. Our Hatsune Miku Art Chair is the ultimate expression of this stubborn intimacy. It is a masterpiece of Hokkaido timber that you won’t just ‘use’; you will claim it as yours, cherishing the warmth and texture that only a lifetime of wooden companionship can provide. Now, here is a portal to an object you’ll want to call ‘mine’: the image below is your link to the special site. If you prefer the cold, impersonal anonymity of mass-produced plastic, do NOT click it. But if you’re ready to start a strictly dedicated relationship with a work of art, go ahead. Make it yours. —— The Hatsune Miku Art Chair.

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!