From melon bread to muskets

Have you ever tried “Melon Pan”? Even though it tastes nothing like melon, it is a staple of Japanese bakeries and famous worldwide as the Japanese bread. As I’ve mentioned in other articles, we Japanese eat as much bread as we do rice. In fact, our word for bread is pan—derived from the Portuguese pão (similar to the Spanish pan and French pain).

Bread arrived in Japan in the 16th century, brought by Portuguese merchants. But along with the yeast and flour, they brought something much more explosive: the rifle.

The day Portuguese merchants cried

In 1543, when those merchants introduced firearms, they were rubbing their hands together in glee. They imagined a future where Japanese warriors would be dependent on European imports for decades.

They couldn’t have been more wrong.

At the time, Japan was a land of master swordsmiths. These metalworking geniuses didn’t just look at the gun; they disassembled it, understood it, and mastered its production within a single year. By the year 1600, the quality of Japanese rifles had surpassed European ones.

This wasn’t just a “nightmare of local competition” in an economic sense; it was a geopolitical shift. The 16th century was the Age of Discovery, with Portugal and Spain expanding their colonial empires across Asia. However, Japan’s massive production capacity and its—fortunate or unfortunate—mastery of firearms through constant civil war made the colonial powers nervous. Instead of Japan being a target for colonization, the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Asia found themselves living in fear of a Japanese invasion.

The rise and fall of the woodworking machine

Japan has always had a terrifying talent for importing an idea and perfecting it. We did it with guns, and 150 years ago, we did it with chairs. When “chair culture” finally arrived in Japan, we built a thriving wooden furniture industry and developed world-class woodworking machines to support it.

But then, history took a turn. Most of those Japanese machine makers pivoted to heavy industries like car manufacturing. Today, the world’s best woodworking CNC machines are mostly Italian. It’s an “uncomfortable truth” for us, though there’s a silver lining: even those fancy Italian machines usually have Japanese precision equipment as their “beating heart.”

The great squeeze: Survival in the global age

Right now, the Japanese furniture industry is caught in a “Great Squeeze” between elite Italian brands and low-cost Asian manufacturers. It feels like a battlefield where we’ve been outmaneuvered.

But if history teaches us anything, it’s that the Japanese spirit thrives when its back is against the wall. Like the swordsmiths who turned a foreign rifle into a masterpiece that shook empires, we are finding our own way to conquer the global market—one perfectly joined piece of wood at a time.

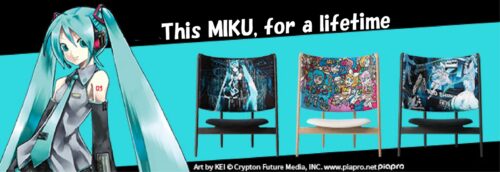

Just as the samurai took a foreign invention and made it a masterpiece that changed history, our “Hatsune Miku Art Chair” takes a global pop icon and infuses her with the soul of traditional Hokkaido craftsmanship. It’s a 21st-century evolution of that same Japanese spirit: taking something the world loves and giving it a level of quality only we can provide. Why not own a piece of this “modern legend” that connects the Age of Discovery with the age of digital art?

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!