The supermarket sorceress

In the Japanese winter, apples are everywhere. While harvested in the autumn, in Northern Japan (Hokkaido and Tohoku), they are stored in “Yukimuro”—warehouses cooled by natural snow. The constant temperature of 0°C and 90% humidity create the perfect environment to make the fruit even sweeter. If you visit Hokkaido in winter, tasting a snow-aged apple is a must.

My wife treats the apple stand like a sacred altar. Watching her select them is like witnessing an ancient ritual. She rotates them with grave intensity, inspecting every millimeter for the slightest flaw. I have never once tasted a difference between her “chosen ones” and the random ones I grab when she isn’t looking.

However, according to my wife, I am the shallow one. She claims that “the act of tasting the apple begins with the selection process itself.” To her, it’s not about logic; it’s a spiritual ceremony. My rational observation that her staring is “meaningless” holds no weight in her world.

The high cost of “Standard” beauty

This obsession with appearance isn’t just a domestic quirk; it’s a systemic crisis. In Japan, 30% of agricultural output is discarded as “non-standard.” Technological advancements, like optical sensors, have only increased food waste by enforcing an impossible standard of “perfect” beauty.

Beauty standards shift with the era and vary by culture. They were supposed to be tools for judging quality, not ends in themselves. When it comes to apples, we know that a slight deviation in shape or color has zero impact on taste. To keep using “visual perfection” as the primary filter is a form of lookism—essentially, it is a “suspension of thought.” Beauty is just a tool for efficient judgment, not an absolute truth. (And I must firmly state: this critique is born of cold logic, not a lingering jealousy toward those who were wildly popular and attractive in their youth.)

The hunter-gatherer’s wisdom

Recently, my view of human history has been shaken by anthropologists like Jared Diamond and Rutger Bregman. They’ve made me wonder: was our “progress” from hunting and gathering to organized farming actually a step forward, or did we trade freedom for rigid, soul-crushing standards?

One thing seems certain: our ancestors must have been far more tolerant of diversity. When you barter for the blessings of nature, you appreciate the life within it. You don’t complain that a root is crooked or a fruit is scarred.

The renaissance of the knot

This brings me back to my own world: wooden furniture. For too long, our industry has acted like a “Supermarket Sorceress,” rejecting any timber with a knot or strong grain as defective.

I’m not suggesting we go “back to nature” and live in caves. But I do wish for a world where we stop splitting hairs over superficial flaws. When you see a knot in a table, you aren’t seeing a “defect”; you are seeing the history of a branch that fought for sunlight.

If we can learn to accept a scarred apple or a knotty piece of oak, we aren’t just reducing waste. We are reclaiming the tolerance we lost somewhere between the forest and the supermarket aisle. Let’s stop looking for perfection and start looking for soul.

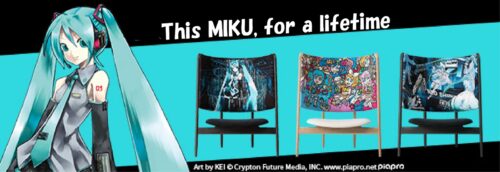

I confess that I’m weary of a world that discards 30% of its soul because it doesn’t meet a ‘standard’ of perfection. At CondeHouse, we don’t act like ‘Supermarket Sorceresses’ rejecting the scars of nature. We believe that a knot in the wood isn’t a defect; it’s a record of a branch that fought for the sun. Our Hatsune Miku Art Chair is born from this same reclamation of tolerance. It isn’t about cold, optical-sensor perfection; it is about the vibrant, turquoise-green soul that lives within the grain of our Hokkaido timber. It is a masterpiece for those who have stopped looking for superficial flaws and started looking for ‘soul.’ Now, here is a portal to a beauty that refuses to be ‘standard’: the image below is your link to the special site. If you prefer the sterile, thought-suspending perfection of the mass-produced, do NOT click it. But if you’re ready to embrace the scars and stories of the real world, go ahead. Claim the extraordinary. —— The Hatsune Miku Art Chair.

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!