The urban predators of Hokkaido

Last year, something strange happened in my hometown, Asahikawa. It wasn’t a virus that closed our riverbeds and forest parks—it was bears.

Traditionally, we believed bears were afraid of humans. We thought they only attacked out of self-defense when accidentally startled. This is why people wore “bear bells” and let off firecrackers—to announce our presence so the bears could run away. But recent incidents have shattered that sense of security. Hungry bears in residential areas are starting to view humans not as a threat to be avoided, but as prey to be hunted.

One of the most chilling cases from last year involved a man delivering newspapers in the early morning. It was discovered that the bear had been seen near his route for several days prior. The bear had been observing him, learning his routine, and eventually targeted him specifically as he moved along the same path at the same time every day. This is no longer “accidental nature”; this is a new, predatory reality.

The collapse of the “buffer zone”

Japan is 70% mountainous. For centuries, the small farming villages at the foot of these mountains acted as a “Satoyama”—a buffer zone where human activity kept the wild at bay.

As Japan’s population declines, these villages are being abandoned. Abandoned rice paddies and orchards have become an “all-you-can-eat” buffet for wildlife. The bears haven’t just regained their territory; they’ve found a paradise of high-calorie human crops. But this paradise is a ticking time bomb.

The paradox of abandonment

When humans stop managing the land, biodiversity actually decreases. In the abandoned forests of these “ghost villages,” aggressive undergrowth like bamboo grass (Sasa) quickly smothers young trees. Without human intervention to thin the woods, the trees that produce nuts and acorns—the primary food for bears—die out.

The result? A desolate, overgrown forest that can no longer support the animals. This is why bears are desperately pushing into our cities. They aren’t returning home; they are fleeing a collapsing ecosystem that we stopped taking care of.

Furniture: The last line of defense

As Erich Fromm once suggested, humans are not separate from nature; we are a part of it. This means that once we have intervened in nature, we have a responsibility to continue that involvement.

At CondeHouse, we make furniture using wood from these forests. You might see cutting trees as “deforestation,” but in a depopulating country like Japan, conscious harvesting is the only way to save the forest. By using the wood, we provide the economic incentive to manage the trees, thin the undergrowth, and maintain the buffer zone that keeps the ecosystem healthy—and the bears where they belong.

Our furniture making is not just a business; it is a defensive line against the destruction that comes from abandonment. We don’t just work with wood; we work to ensure the forest remains a home for both bears and humans, separated by a healthy, managed boundary.

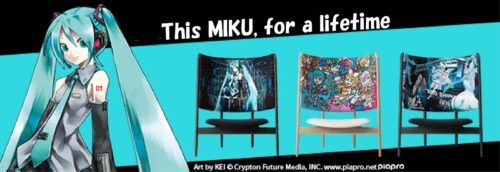

A bear hunting in the city is a sign of a world out of balance. True beauty, however, is found where humans and nature exist in harmony, respecting the boundaries between them. Our “Hatsune Miku Art Chair” is a symbol of that balance. It is crafted from the very wood that must be harvested to keep our forests healthy and our “buffer zones” intact. By choosing a piece of furniture born from responsible forestry, you aren’t just decorating a room; you are supporting the survival of the Japanese forest and the safety of its people. Why not own a chair that tells a story of protection, tradition, and the courage to stay involved with the natural world?

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!