The Sumo of sorrows: Welcome to Hebocon

In a world obsessed with AI, high-speed automation, and surgical precision, Japan holds an annual celebration of the exact opposite: Hebocon.

The name is derived from “heboi,” a Japanese term for something clumsy, incompetent, or downright pathetic. The rules are strict: you must be a complete amateur. If you accidentally build something functional or—god forbid—technically impressive, you lose points.

At Hebocon, you will witness robots made of cardboard and vibrating toothbrushes that fall apart before they even touch their opponent. It is a “Sumo of Sorrows.” When adults without an ounce of engineering skill take their useless machines seriously, the result is more moving (and certainly more hilarious) than any Boston Dynamics demonstration.

Take, for example, the participant who tapes a hand-drawn demonic face to their machine in a desperate bid for intimidation. As this paper-faced entity wobbles helplessly across the floor, it evokes a sense of dread that transcends mere comedy—it is a haunting spectacle of unearned confidence. Inevitably, the “tactical” components added based on the creator’s inexplicable obsessions become the very anchors that sink the ship, causing the machine (if one can even call it that) to seize up or self-destruct.

Hebocon is a profound rejection of the cult of efficiency. Nay, it is a grand, tragic microcosm of the human condition itself: a spectacle where we all struggle desperately for happiness, only for our own misguided efforts to become the very obstacles that defeat us.

The animism of technology: Why we don’t fear the robot

Why does Japan embrace such technological tragedy? Because in our cultural software, a robot doesn’t need to be “useful” to be loved.

Western media often portrays robots as either sleek icons of power (Iron Man) or harbingers of the apocalypse (The Terminator). In Japan, our foundational robot is Doraemon—a blue, earless robot cat from the future who is remarkably bad at his job. He’s clumsy, he’s insecure, and his gadgets often backfire.

He is not a tool; he is a companion.

This mindset explains why we created AIBO, ASIMO, and Pepper—machines that were arguably “useless” from a productivity standpoint but excelled at being “present.” We apply a form of modern animism to our machines. If it has a face and a personality, it has a soul, no matter how heboi its hardware may be.

From the virtual to the physical: The Art of Miku

This acceptance of the “non-functional but meaningful” is the bridge to the virtual idol. Hatsune Miku is a digital entity—a voice synthesizer with no physical body—yet she fills stadiums. She exists in the collective imagination, a masterpiece of the “useless” in the sense that she serves no industrial purpose other than to inspire.

As a furniture maker in Hokkaido (the same birthplace as Miku), we decided to perform an act of “Physicalization.” We didn’t want to make a chair that was merely a tool for sitting. That would be too efficient, too boring.

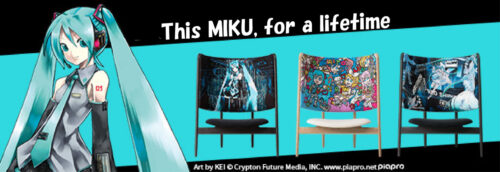

We partnered with the ART OF MIKU project to create a lounge chair that acts as a canvas for contemporary art. We took the finest Hokkaido wood, crafted it with artisan precision, and then—in a move that might baffle a pure functionalist—printed vibrant pop art directly onto it.

We even added a nameplate made from recycled scallop shells, signed by the artist. Is it necessary for the chair to function? Absolutely not. But like a clumsy robot or a virtual singer, it provides something that a “useful” chair never could: a soul.

I confess that I love the ‘heboi’—the clumsy, the technically pathetic, and the wonderfully useless—because in a world of cold efficiency, only the ‘useless’ has enough space for a soul. At CondeHouse, we realized that a chair that is merely a tool for sitting is as boring as a robot without a face. That’s why we created the Hatsune Miku Art Chair. It is our grand, physicalized act of modern animism: we took the finest Hokkaido timber and, defying every law of ‘functionalist’ furniture, turned it into a vibrant canvas for a digital legend. With its recycled scallop-shell nameplate and bold pop-art skin, it doesn’t just support your body; it inspires your imagination. It is a masterpiece that serves no ‘industrial’ purpose other than to be loved. Now, here is a portal to a creation that is brilliantly, beautifully ‘useless’: the image below is your link to the special site. If you prefer the sterile, efficient chairs of the status quo, do NOT click it. But if you’re ready to own a piece of furniture with a soul, go ahead. Take your seat in the extraordinary. —— The Hatsune Miku Art Chair.

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!