The stolen season: What COVID took away

In 2020, COVID took away the Tokyo Olympics. But it also stole something far more pervasive: the Japanese summer festivals (Natsu Matsuri). Over 300,000 Natsu Matsuri are typically held across Japan in late August. It’s a magical time, especially for kids, marked by cheap candies, tempting food stands, and fireworks. It’s the seasonal climax before the end of summer vacation. The pandemic didn’t just rob us of this tradition; it robbed us of the very sense of the changing seasons.

Before diving into the chaos of the festivals, we need to address their root: the Japanese religious view.

The paradox of Japanese faith: More shrines than convenience stores

Summer festivals are fundamentally religious events—originally held to welcome and then send back the spirits of ancestors.

Anyone who has attended a Japanese festival probably finds it impossible to believe that it’s a religious event. Kids are obsessed with food stands and games, young people are desperately trying to look good for the object of their affection, and adults are simply trying to chug cold beer. It is, perhaps, a strange religion—one whose lack of global endorsement is utterly baffling.

Japanese people are often described as non-religious, and we generally agree. This is because our main religions (Shinto and Buddhism) lack strict, dogmatic doctrines. This is why we seamlessly adopt Christmas, and why Halloween’s popularity exploded without any moral hesitation.

However, I argue that we are, in fact, intensely religious, just not strictly dogmatic. Consider the facts:

- About 70% of the population visits a shrine or temple in the first three days of the new year.

- The total number of shrines and temples exceeds 150,000.

- The total number of convenience stores (7-11, Family Mart, Lawson, etc.) is still less than 60,000.

We have three times as many places to pray to the gods as we do places to buy cheap instant noodles and beer. This extreme devotion to convenience is often cited as a sign of modernity, but I find the comparison unsettling. We are a nation that is both deeply pragmatic and quietly spiritual.

The real reason we dance: Workplace harmony

Many people may forget the original, sacred meaning of the festival, but I don’t think that’s the serious problem. The modern function is far more pragmatic: It’s a crucial, annual opportunity to develop and maintain local and workplace relationships.

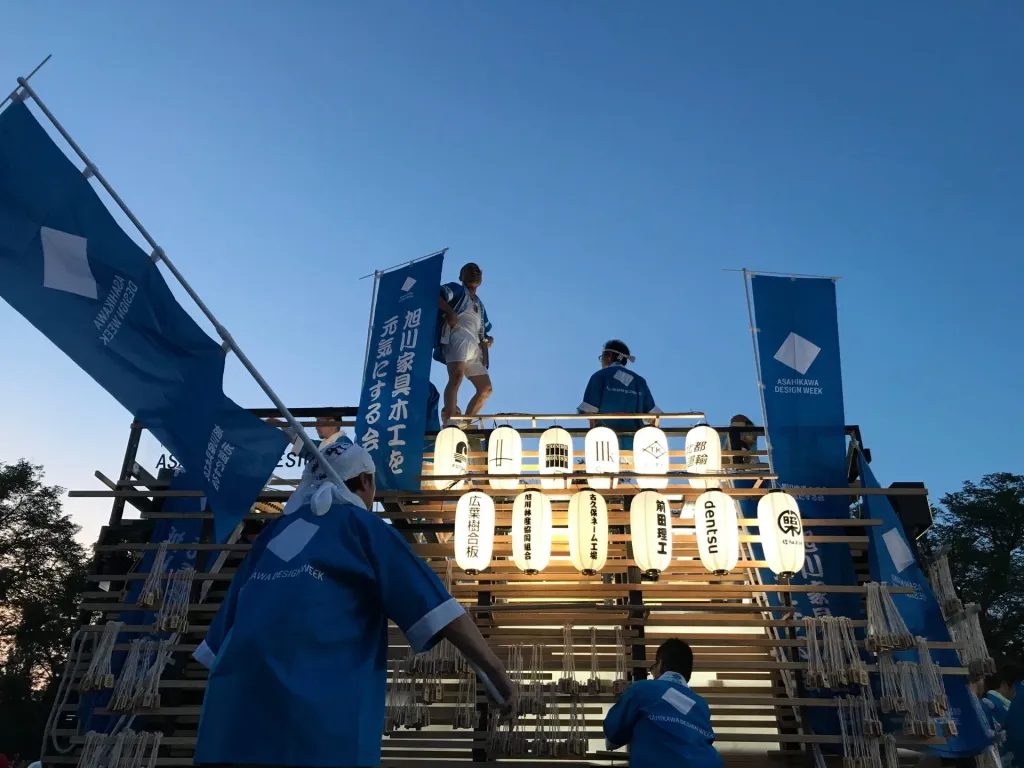

CondeHouse participates in our local festival by constructing and pulling a portable shrine float (mikoshi) using our own woodworking skills. We pull the float through the main street, perform intentionally comical dances (to break the ice), and then hold a necessary after-party.

Here in Hokkaido, summer is painfully short, making the Natsu Matsuri even more vital. We are not just enhancing relationships in the local community; we are engaging in a necessary ritual for workplace harmony and, just as importantly, convincing ourselves that summer is finally, truly over.

It’s a worn-out phrase, but it is deeply true: we always realize the importance of something—whether it’s an ancestor-sending ritual or a chaotic team dance—only after losing it.

I confess that I find Japan’s ‘religion of convenience’ fascinating—where we have three times as many shrines as 7-Elevens, yet we only realize the sacredness of our chaotic festivals once they are gone. At CondeHouse, we understand that true harmony isn’t found in a textbook; it’s built through the shared ritual of creation. Our Hatsune Miku Art Chair is our modern ‘portable shrine’ (mikoshi)—a masterpiece born from the same Hokkaido woodworking skills we use to build our festival floats. It’s a bold, turquoise-green celebration of a digital icon, designed to bring a sense of the extraordinary into your quiet, daily life. It’s not just a seat; it’s a ritual of peace and joy for your home. Now, here is a portal to your own private festival: the image below is your link to the special site. If you prefer the predictable, prayer-less sterility of the ordinary, do NOT click it. But if you’re ready to invite a little sacred chaos and artisan soul into your living room, go ahead. Join the celebration. —— The Hatsune Miku Art Chair.

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!

Comments

List of comments (1)

[…] Japanese Summer Festivals […]