The Stephen King of zoos

If you look at world zoo rankings, you’ll see the heavy hitters: San Diego, Singapore, and right here in our hometown—Asahiyama Zoo. But if you had visited in the early 90s, when I was a child, you would have found a scene straight out of a Stephen King novel.

Back then, every elementary school student in Asahikawa visited the zoo for field trips. It was a place where interest went to die. The outdated amusement park rides squeaked in the wind, and the animals lay as still as taxidermy. Once we finished our lunch boxes, there was absolutely nothing to do. I still remember the suffocating boredom of waiting for the bus.

It was a hellish tableau: inside the cages, animals were left to wallow in lethargy; outside the cages, children had lost all curiosity and were merely counting the minutes until they could leave. It was more horrifying than anything King could write. In 1995, however, a new director decided that if the zoo was going to die, it should at least go down fighting.

The art of the behavioral exhibit

The new director’s diagnosis was sharp: “Our staff are experts at keeping animals alive, but they are amateurs at making customers feel alive.” They stopped “showing” animals and started “exhibiting their spirit” through what is now famous as the “Behavioral Exhibit.” Suddenly, penguins weren’t just waddling on ice; they were “flying” through underwater tunnels. Seals weren’t just bobbing in a tank; they were zipping up and down through transparent cylinders. You could walk under a snow leopard and see the surprisingly hairy soles of its paws as it stalked above you.

Taking advantage of Asahikawa’s heavy winters, the zoo even lets the penguins out of their enclosures for daily “strolls” across the soft snow, which protects their feet while delighting the crowds. And when you see the wolves racing through a forest-like habitat so vast they almost disappear, it forces you to confront a heavy historical weight—the responsibility of having hunted the Japanese wolf to extinction. The zoo is no longer a place to “pass the time”; it is a place to confront the raw, beautiful, and sometimes tragic reality of life.

The “Factory Exhibit”: Our own rebirth

Watching the success of Asahiyama Zoo has deeply inspired us at CondeHouse. We realized that our factories shouldn’t just be places where “work happens”—they should be stages where “craftsmanship is performed.”

We are currently redesigning our headquarters and factory tours to invite more visitors into our world. Furniture making and zookeeping may differ, but our core mission is the same: to move people’s hearts.

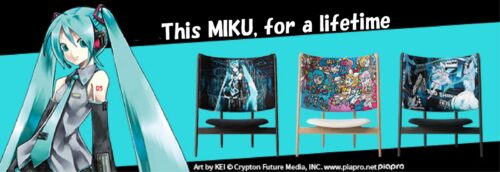

We don’t just want to show you a finished chair; we want you to see the “behavioral exhibit” of our artisans—the way they read the grain of the wood, the precision of their assembly, and the soul they pour into every joint. We want our headquarters to be a destination that entertains and inspires, mirroring the vibrant, living spirit of the flying penguins just down the road.

Just as a zoo captures the vibrant spirit of life, a great piece of furniture should possess a soul that feels alive in your home. Why settle for a static object when you can own a piece that breathes with the history of its craftsmanship?

Shungo Ijima

Global Connector | Reformed Bureaucrat | Professional Over-Thinker

After years of navigating the rigid hallways of Japan’s Ministry of Finance and surviving an MBA, he made a life-changing realization: spreadsheets are soulless, and wood has much better stories to tell.

Currently an Executive at CondeHouse, he travels the world decoding the “hidden DNA” of Japanese culture—though, in his travels, he’s becoming increasingly more skilled at decoding how to find the cheapest hotels than actual cultural mysteries.

He has a peculiar talent for finding deep philosophical meaning in things most people ignore as meaningless (and to be fair, they are often actually meaningless). He doesn’t just sell furniture; he’s on a mission to explain Japan to the world, one intellectually over-analyzed observation at a time. He writes for the curious, the skeptical, and anyone who suspects that a chair might actually be a manifesto in disguise.

Follow his journey as he bridges the gap between high-finance logic and the chaotic art of living!